Chapter 16. Variables: Scopes, Environments, and Closures

This chapter first explains how to use variables and then goes into detail on how they work (environments, closures, etc.).

Declaring a Variable

In JavaScript, you declare a variable via a var statement before you use it:

varfoo;foo=3;// OK, has been declaredbar=5;// not OK, an undeclared variable

You can also combine a declaration with an assignment, to immediately initialize a variable:

varfoo=3;

The value of an uninitialized variable is undefined:

> var x; > x undefined

Background: Static Versus Dynamic

There are two angles from which you can examine the workings of a program:

- Statically (or lexically)

You examine the program as it exists in source code, without running it. Given the following code, we can make the static assertion that function

gis nested inside functionf:functionf(){functiong(){}}The adjective lexical is used synonymously with static, because both pertain to the lexicon (the words, the source) of the program.

- Dynamically

You examine what happens while executing the program (“at runtime”). Given the following code:

functiong(){}functionf(){g();}when we call

f(), it callsg(). During runtime,gbeing called byfrepresents a dynamic relationship.

Background: The Scope of a Variable

For the rest of this chapter, you should understand the following concepts:

- The scope of a variable

The scope of a variable are the locations where it is accessible. For example:

functionfoo(){varx;}Here, the direct scope of

xis the functionfoo().- Lexical scoping

- Variables in JavaScript are lexically scoped, so the static structure of a program determines the scope of a variable (it is not influenced by, say, where a function is called from).

- Nested scopes

If scopes are nested within the direct scope of a variable, then the variable is accessible in all of those scopes:

functionfoo(arg){functionbar(){console.log('arg: '+arg);}bar();}console.log(foo('hello'));// arg: helloThe direct scope of

argisfoo(), but it is also accessible in the nested scopebar(). With regard to nesting,foo()is the outer scope andbar()is the inner scope.- Shadowing

If a scope declares a variable that has the same name as one in a surrounding scope, access to the outer variable is blocked in the inner scope and all scopes nested inside it. Changes to the inner variable do not affect the outer variable, which is accessible again after the inner scope is left:

varx="global";functionf(){varx="local";console.log(x);// local}f();console.log(x);// globalInside the function

f(), the globalxis shadowed by a localx.

Variables Are Function-Scoped

Most mainstream languages are block-scoped: variables “live inside” the innermost surrounding code block. Here is an example from Java:

publicstaticvoidmain(String[]args){{// block startsintfoo=4;}// block endsSystem.out.println(foo);// Error: cannot find symbol}

In the preceding code, the variable foo is accessible only inside the block that directly surrounds it. If we try to access it after the end of the block, we get a compilation error.

In contrast, JavaScript’s variables are function-scoped: only functions introduce new scopes; blocks are ignored when it comes to scoping. For example:

functionmain(){{// block startsvarfoo=4;}// block endsconsole.log(foo);// 4}

Put another way, foo is accessible within all of main(), not just inside the block.

Variable Declarations Are Hoisted

JavaScript hoists all variable declarations, it moves them to the beginning of their direct scopes. This makes it clear what happens if a variable is accessed before it has been declared:

functionf(){console.log(bar);// undefinedvarbar='abc';console.log(bar);// abc}

We can see that the variable bar already exists in the first line of f(), but it does not have a value yet; that is, the declaration has been hoisted, but not the assignment. JavaScript executes f() as if its code were:

functionf(){varbar;console.log(bar);// undefinedbar='abc';console.log(bar);// abc}

If you declare a variable that has already been declared, nothing happens (the variable’s value is unchanged):

> var x = 123; > var x; > x 123

Each function declaration is also hoisted, but in a slightly different manner. The complete function is hoisted, not just the creation of the variable in which it is stored (see Hoisting).

Best practice: be aware of hoisting, but don’t be scared of it

Some JavaScript style guides recommend that you only put variable declarations at the beginning of a function, in order to avoid being tricked by hoisting. If your function is relatively small (which it should be anyway), then you can afford to relax that rule a bit and declare variables close to where they are used (e.g., inside a for loop). That better encapsulates pieces of code. Obviously, you should be aware that that encapsulation is only conceptual, because function-wide hoisting still happens.

Introducing a New Scope via an IIFE

You typically introduce a new scope to restrict the lifetime of a variable. One example where you may want to do so is the “then” part of an if statement: it is executed only if the condition holds; and if it exclusively uses helper variables, we don’t want them to “leak out” into the surrounding scope:

functionf(){if(condition){vartmp=...;...}// tmp still exists here// => not what we want}

If you want to introduce a new scope for the then block, you can define a function and immediately invoke it. This is a workaround, a simulation of block scoping:

functionf(){if(condition){(function(){// open blockvartmp=...;...}());// close block}}

This is a common pattern in JavaScript. Ben Alman suggested it be called immediately invoked function expression (IIFE, pronounced “iffy”). In general, an IIFE looks like this:

(function(){// open IIFE// inside IIFE}());// close IIFE

Here are some things to note about an IIFE:

- It is immediately invoked

- The parentheses following the closing brace of the function immediately invoke it. That means its body is executed right away.

- It must be an expression

-

If a statement starts with the keyword

function, the parser expects it to be a function declaration (see Expressions Versus Statements). But a function declaration cannot be immediately invoked. Thus, we tell the parser that the keywordfunctionis the beginning of a function expression by starting the statement with an open parenthesis. Inside parentheses, there can only be expressions. - The trailing semicolon is required

If you forget it between two IIFEs, then your code won’t work anymore:

(function(){...}())// no semicolon(function(){...}());The preceding code is interpreted as a function call—the first IIFE (including the parentheses) is the function to be called, and the second IIFE is the parameter.

Note

An IIFE incurs costs (both cognitively and performance-wise), so it rarely makes sense to use it inside an if statement. The preceding example was chosen for didactic reasons.

IIFE Variation: Prefix Operators

You can also enforce the expression context via prefix operators. For example, you can do so via the logical Not operator:

!function(){// open IIFE// inside IIFE}();// close IIFE

or via the void operator (see The void Operator):

voidfunction(){// open IIFE// inside IIFE}();// close IIFE

The advantage of using prefix operators is that forgetting the terminating semicolon does not cause trouble.

IIFE Variation: Already Inside Expression Context

Note that enforcing the expression context for an IIFE is not necessary, if you are already in the expression context. Then you need no parentheses or prefix operators. For example:

varFile=function(){// open IIFEvarUNTITLED='Untitled';functionFile(name){this.name=name||UNTITLED;}returnFile;}();// close IIFE

In the preceding example, there are two different variables that have the name File. On one hand, there is the function that is only directly accessible inside the IIFE. On the other hand, there is the variable that is declared in the first line. It is assigned the value that is returned in the IIFE.

IIFE Variation: An IIFE with Parameters

You can use parameters to define variables for the inside of the IIFE:

varx=23;(function(twice){console.log(twice);}(x*2));

This is similar to:

varx=23;(function(){vartwice=x*2;console.log(twice);}());

IIFE Applications

An IIFE enables you to attach private data to a function. Then you don’t have to declare a global variable and can tightly package the function with its state. You avoid polluting the global namespace:

varsetValue=function(){varprevValue;returnfunction(value){// define setValueif(value!==prevValue){console.log('Changed: '+value);prevValue=value;}};}();

Other applications of IIFEs are mentioned elsewhere in this book:

- Avoiding global variables; hiding variables from global scope (see Best Practice: Avoid Creating Global Variables)

- Creating fresh environments; avoiding sharing (see Pitfall: Inadvertently Sharing an Environment)

- Keeping global data private to all of a constructor (see Keeping global data private to all of a constructor)

- Attaching global data to a singleton object (see Attaching private global data to a singleton object)

- Attaching global data to a method (see Attaching global data to a method)

Global Variables

The scope containing all of a program is called global scope or program scope. This is the scope you are in when entering a script (be it a <script> tag in a web page or be it a .js file). Inside the global scope, you can create a nested scope by defining a function. Inside such a function, you can again nest scopes. Each scope has access to its own variables and to the variables in the scopes that surround it. As the global scope surrounds all other scopes, its variables can be accessed everywhere:

// here we are in global scopevarglobalVariable='xyz';functionf(){varlocalVariable=true;functiong(){varanotherLocalVariable=123;// All variables of surround scopes are accessiblelocalVariable=false;globalVariable='abc';}}// here we are again in global scope

Best Practice: Avoid Creating Global Variables

Global variables have two disadvantages. First, pieces of software that rely on global variables are subject to side effects; they are less robust, behave less predictably, and are less reusable.

Second, all of the JavaScript on a web page shares the same global variables: your code, built-ins, analytics code, social media buttons, and so on. That means that name clashes can become a problem. That is why it is best to hide as many variables from the global scope as possible. For example, don’t do this:

<!-- Don’t do this --><script>// Global scopevartmp=generateData();processData(tmp);persistData(tmp);</script>

The variable tmp becomes global, because its declaration is executed in global scope. But it is only used locally. Hence, we can use an IIFE (see Introducing a New Scope via an IIFE) to hide it inside a nested scope:

<script>(function(){// open IIFE// Local scopevartmp=generateData();processData(tmp);persistData(tmp);}());// close IIFE</script>

Module Systems Lead to Fewer Globals

Thankfully, module systems (see Module Systems) mostly eliminate the problem of global variables, because modules don’t interface via the global scope and because each module has its own scope for module-global variables.

The Global Object

The ECMAScript specification uses the internal data structure environment to store variables (see Environments: Managing Variables). The language has the somewhat unusual feature of making the environment for global variables accessible via an object, the so-called global object. The global object can be used to create, read, and change global variables. In global scope, this points to it:

> var foo = 'hello'; > this.foo // read global variable 'hello' > this.bar = 'world'; // create global variable > bar 'world'

Note that the global object has prototypes. If you want to list all of its (own and inherited) properties, you need a function such as getAllPropertyNames() from Listing All Property Keys:

> getAllPropertyNames(window).sort().slice(0, 5) [ 'AnalyserNode', 'Array', 'ArrayBuffer', 'Attr', 'Audio' ]

JavaScript creator Brendan Eich considers the global object one of his “biggest regrets”. It affects performance negatively, makes the implementation of variable scoping more complicated, and leads to less modular code.

Cross-Platform Considerations

Browsers and Node.js have global variables for referring to the global object. Unfortunately, they are different:

-

Browsers include

window, which is standardized as part of the Document Object Model (DOM), not as part of ECMAScript 5. There is one global object per frame or window. -

Node.js contains

global, which is a Node.js-specific variable. Each module has its own scope in whichthispoints to an object with that scope’s variables. Accordingly,thisandglobalare different inside modules.

On both platforms, this refers to the global object, but only when you are in global scope. That is almost never the case on Node.js. If you want to access the global object in a cross-platform manner, you can use a pattern such as the following:

(function(glob){// glob points to global object}(typeofwindow!=='undefined'?window:global));

From now on, I use window to refer to the global object, but in cross-platform code, you should use the preceding pattern and glob instead.

Use Cases for window

This section describes use cases for accessing global variables via window. But the general rule is: avoid doing that as much as you can.

Use case: marking global variables

The prefix window is a visual clue that code is referring to a global variable and not to a local one:

varfoo=123;(function(){console.log(window.foo);// 123}());

However, this makes your code brittle. It ceases to work as soon as you move foo from global scope to another surrounding scope:

(function(){varfoo=123;console.log(window.foo);// undefined}());

Thus, it is better to refer to foo as a variable, not as a property of window. If you want to make it obvious that foo is a global or global-like variable, you can add a name prefix such as g_:

varg_foo=123;(function(){console.log(g_foo);}());

Use case: built-ins

I prefer not to refer to built-in global variables via window. They are well-known names, so you gain little from an indicator that they are global. And the prefixed window adds clutter:

window.isNaN(...)// noisNaN(...)// yes

Use case: style checkers

When you are working with a style checking tool such as JSLint and JSHint, using window means that you don’t get an error when referring to a global variable that is not declared in the current file. However, both tools provide ways to tell them about such variables and prevent such errors (search for “global variable” in their documentation).

Use case: checking whether a global variable exists

It’s not a frequent use case, but shims and polyfills especially (see Shims Versus Polyfills) need to check whether a global variable someVariable exists. In that case, window helps:

if(window.someVariable){...}

This is a safe way of performing this check. The following statement throws an exception if someVariable has not been declared:

// Don’t do thisif(someVariable){...}

There are two additional ways in which you can check via window; they are roughly equivalent, but a little more explicit:

if(window.someVariable!==undefined){...}if('someVariable'inwindow){...}

The general way of checking whether a variable exists (and has a value) is via typeof (see typeof: Categorizing Primitives):

if(typeofsomeVariable!=='undefined'){...}

Use case: creating things in global scope

window lets you add things to the global scope (even if you are in a nested scope), and it lets you do so conditionally:

if(!window.someApiFunction){window.someApiFunction=...;}

It is normally best to add things to the global scope via var, while you are in the global scope. However, window provides a clean way of making additions conditionally.

Environments: Managing Variables

Tip

Environments are an advanced topic. They are a detail of JavaScript’s internals. Read this section if you want to get a deeper understanding of how variables work.

Variables come into existence when program execution enters their scope. Then they need storage space. The data structure that provides that storage space is called an environment in JavaScript. It maps variable names to values. Its structure is very similar to that of JavaScript objects. Environments sometimes live on after you leave their scope. Therefore, they are stored on a heap, not on a stack.

Variables are passed on in two ways. There are two dimensions to them, if you will:

- Dynamic dimension: invoking functions

functionfac(n){if(n<=1){return1;}returnn*fac(n-1);}- Lexical (static) dimension: staying connected to your surrounding scopes

No matter how often a function is called, it always needs access to both its own (fresh) local variables and the variables of the surrounding scopes. For example, the following function,

doNTimes, has a helper function,doNTimesRec, inside it. WhendoNTimesReccalls itself several times, a new environment is created each time. However,doNTimesRecalso stays connected to the single environment ofdoNTimesduring those calls (similar to all functions sharing a single global environment).doNTimesRecneeds that connection to accessactionin line (1):functiondoNTimes(n,action){functiondoNTimesRec(x){if(x>=1){action();// (1)doNTimesRec(x-1);}}doNTimesRec(n);}

These two dimensions are handled as follows:

- Dynamic dimension: stack of execution contexts

- Each time a function is invoked, a new environment is created to map identifiers (of parameters and variables) to values. To handle recursion, execution contexts—references to environments—are managed in a stack. That stack mirrors the call stack.

- Lexical dimension: chain of environments

To resolve an identifier, the complete environment chain is traversed, starting with the active environment.

Let’s look at an example:

functionmyFunction(myParam){varmyVar=123;returnmyFloat;}varmyFloat=1.3;// Step 1myFunction('abc');// Step 2

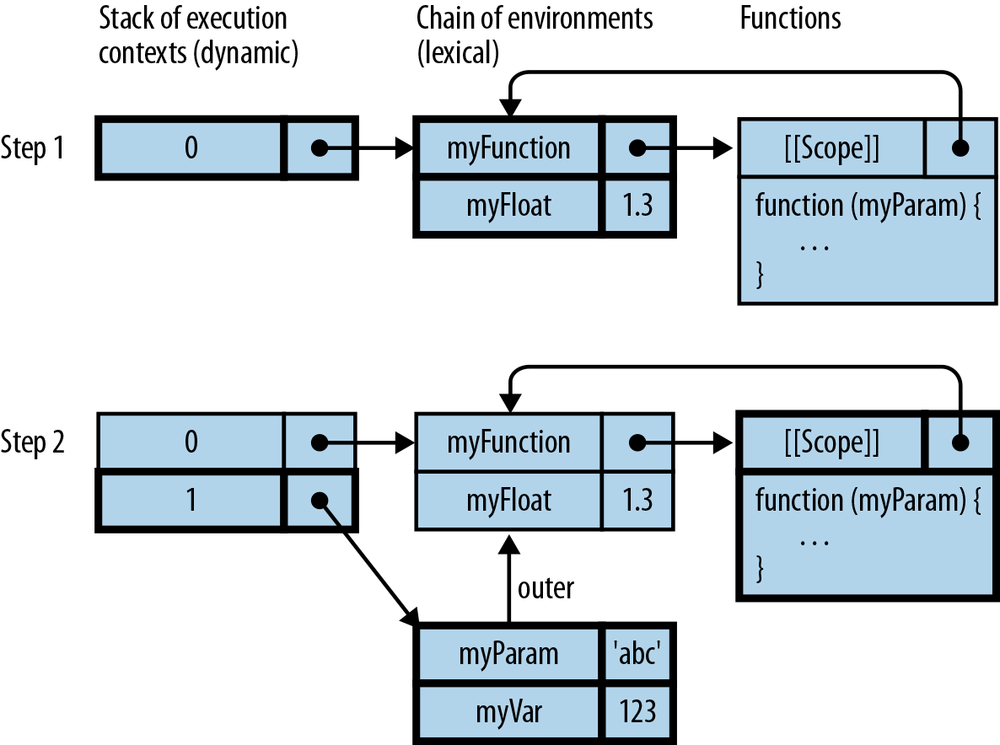

Figure 16-1 illustrates what happens when the preceding code is executed:

-

myFunctionandmyFloathave been stored in the global environment (#0). Note that thefunctionobject referred to bymyFunctionpoints to its scope (the global scope) via the internal property[[Scope]]. -

For the execution of

myFunction('abc'), a new environment (#1) is created that holds the parameter and the local variable. It refers to its outer environment viaouter(which is initialized frommyFunction.[[Scope]]). Thanks to the outer environment,myFunctioncan accessmyFloat.

Closures: Functions Stay Connected to Their Birth Scopes

If a function leaves the scope in which it was created, it stays connected to the variables of that scope (and of the surrounding scopes). For example:

functioncreateInc(startValue){returnfunction(step){startValue+=step;returnstartValue;};}

The function returned by createInc() does not lose its connection to startValue—the variable provides the function with state that persists across function calls:

> var inc = createInc(5); > inc(1) 6 > inc(2) 8

A closure is a function plus the connection to the scope in which the function was created. The name stems from the fact that a closure “closes over” the free variables of a function. A variable is free if it is not declared within the function—that is, if it comes “from outside.”

Handling Closures via Environments

Tip

This is an advanced section that goes deeper into how closures work. You should be familiar with environments (review Environments: Managing Variables).

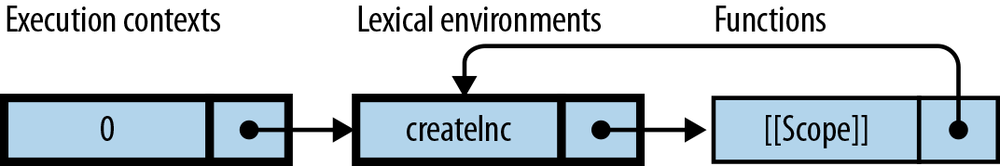

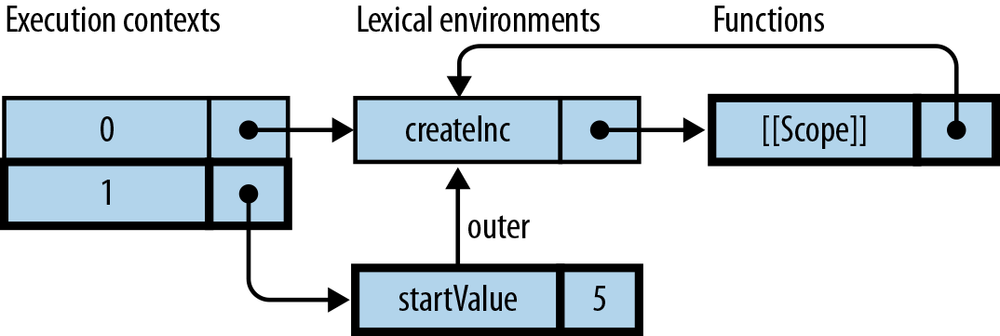

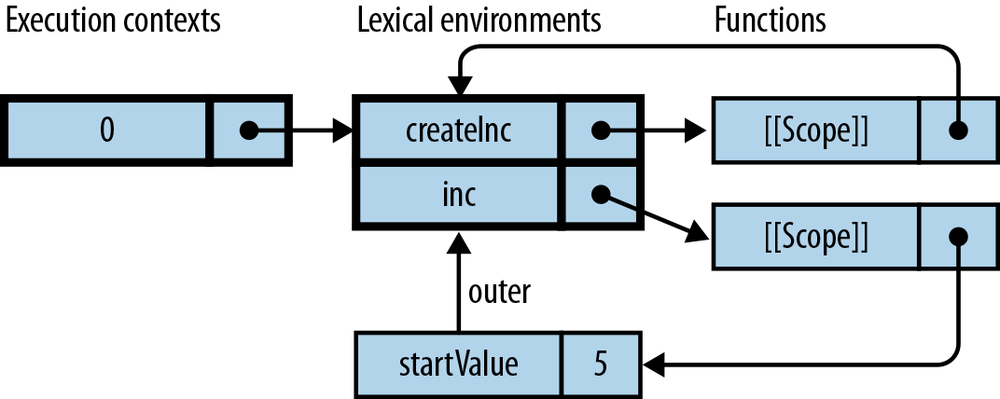

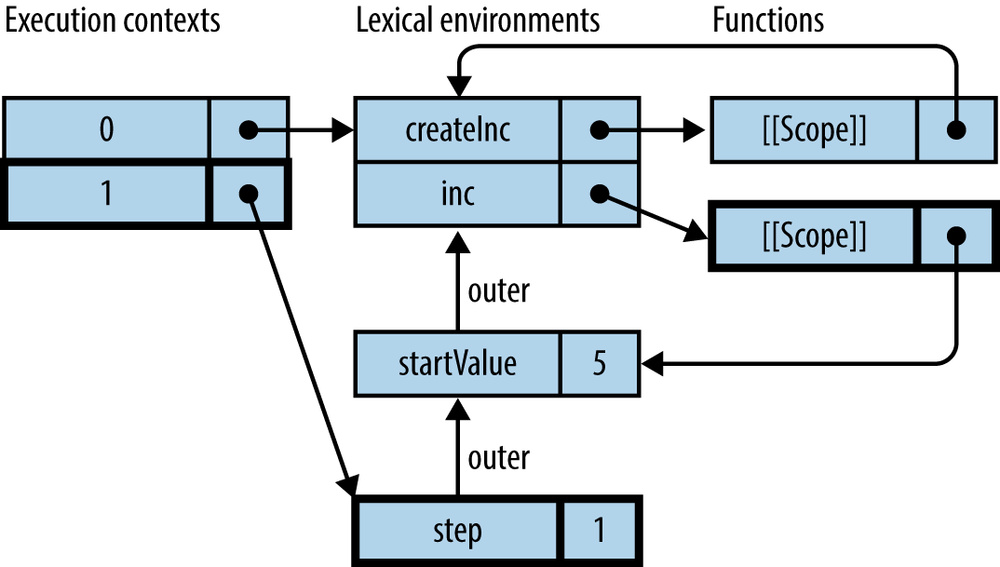

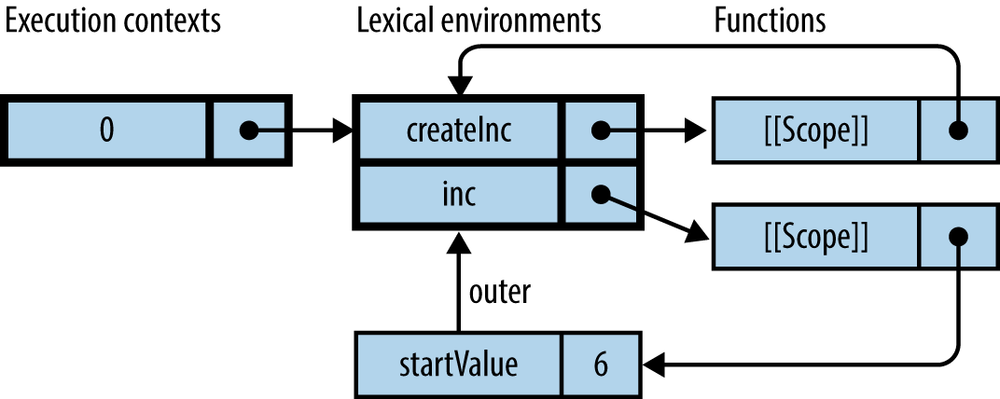

A closure is an example of an environment surviving after execution has left its scope. To illustrate how closures work, let’s examine the previous interaction with createInc() and split it up into four steps (during each step, the active execution context and its environment are highlighted; if a function is active, it is highlighted, too):

This step takes place before the interaction, and after the evaluation of the function declaration of

createInc. An entry forcreateInchas been added to the global environment (#0) and points to a function object.This step occurs during the execution of the function call

createInc(5). A fresh environment (#1) forcreateIncis created and pushed onto the stack. Its outer environment is the global environment (the same ascreateInc.[[Scope]]). The environment holds the parameterstartValue.This step happens after the assignment to

inc. After we returned fromcreateInc, the execution context pointing to its environment was removed from the stack, but the environment still exists on the heap, becauseinc.[[Scope]]refers to it.incis a closure (function plus birth environment).This step takes place during the execution of

inc(1). A new environment (#1) has been created and an execution context pointing to it has been pushed onto the stack. Its outer environment is the[[Scope]]ofinc. The outer environment givesincaccess tostartValue.This step happens after the execution of

inc(1). No reference (execution context,outerfield, or[[Scope]]) points toinc’s environment, anymore. It is therefore not needed and can be removed from the heap.

Pitfall: Inadvertently Sharing an Environment

Sometimes the behavior of functions you create is influenced by a variable in the current scope.

In JavaScript, that can be problematic, because each function should work with the value that the variable had when the function was created. However, due to functions being closures, the function will always work with the current value of the variable. In for loops, that can prevent things from working properly. An example will make things clearer:

functionf(){varresult=[];for(vari=0;i<3;i++){varfunc=function(){returni;};result.push(func);}returnresult;}console.log(f()[1]());// 3

f returns an array with three functions in it. All of these functions can still access the environment of f and thus i. In fact, they share the same environment. Alas, after the loop is finished, i has the value 3 in that environment. Therefore, all functions return 3.

This is not what we want. To fix things, we need to make a snapshot of the index i before creating a function that uses it. In other words, we want to package each function with the value that i had at the time of the function’s creation. We therefore take the following steps:

- Create a new environment for each function in the returned array.

- Store (a copy of) the current value of i in that environment.

Only functions create environments, so we use an IIFE (see Introducing a New Scope via an IIFE) to accomplish step 1:

functionf(){varresult=[];for(vari=0;i<3;i++){(function(){// step 1: IIFEvarpos=i;// step 2: copyvarfunc=function(){returnpos;};result.push(func);}());}returnresult;}console.log(f()[1]());// 1

Note that the example has real-world relevance, because similar scenarios arise when you add event handlers to DOM elements via loops.