10 Consoles: interactive JavaScript command lines

10.1 Trying out JavaScript code

You have many options for quickly running pieces of JavaScript code. The following subsections describe a few of them.

10.1.1 Browser consoles

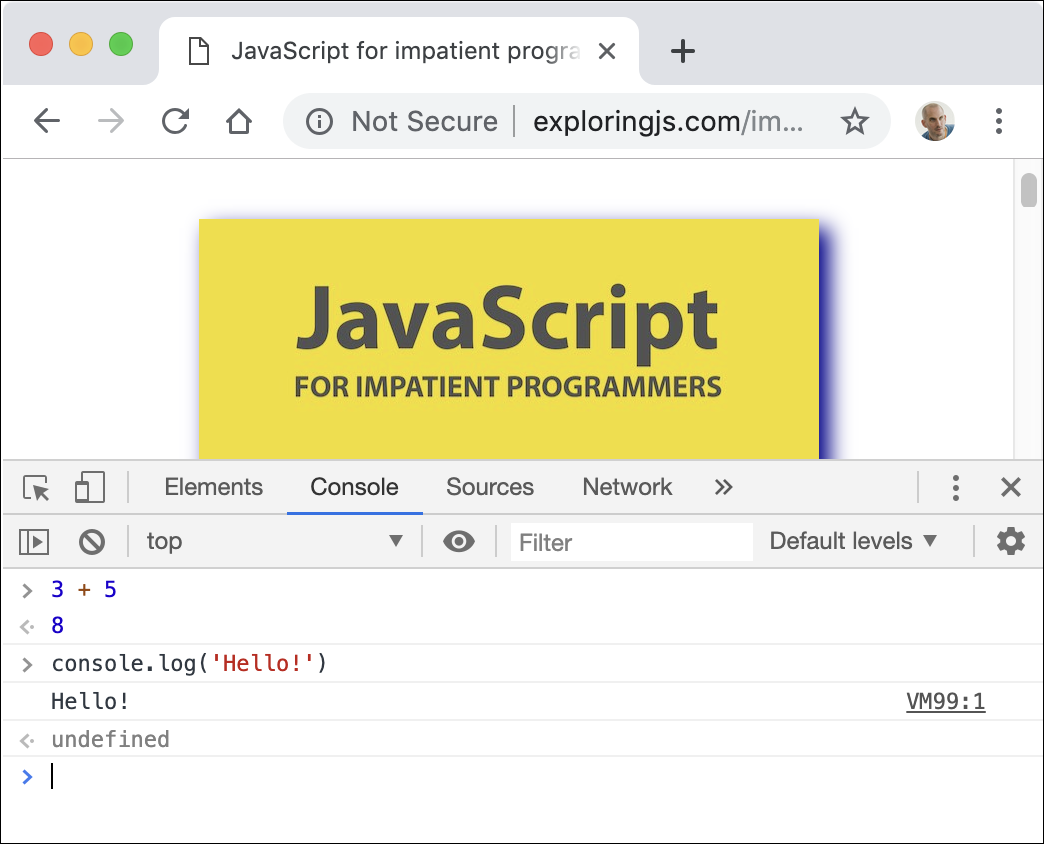

Web browsers have so-called consoles: interactive command lines to which you can print text via console.log() and where you can run pieces of code. How to open the console differs from browser to browser. Figure 10.1 shows the console of Google Chrome.

To find out how to open the console in your web browser, you can do a web search for “console «name-of-your-browser»”. These are pages for a few commonly used web browsers:

Figure 10.1: The console of the web browser “Google Chrome” is open (in the bottom half of window) while visiting a web page.

10.1.2 The Node.js REPL

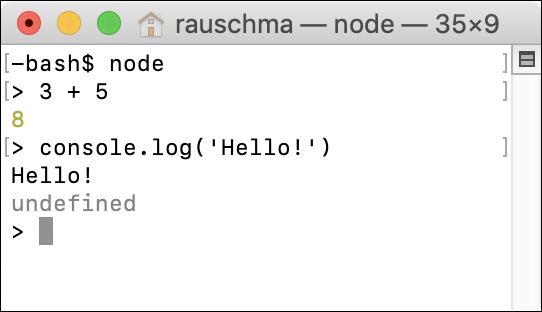

REPL stands for read-eval-print loop and basically means command line. To use it, you must first start Node.js from an operating system command line, via the command node. Then an interaction with it looks as depicted in figure 10.2: The text after > is input from the user; everything else is output from Node.js.

Figure 10.2: Starting and using the Node.js REPL (interactive command line).

Reading: REPL interactions

I occasionally demonstrate JavaScript via REPL interactions. Then I also use greater-than symbols (>) to mark input – for example:

> 3 + 5

8

10.1.3 Other options

Other options include:

-

There are many web apps that let you experiment with JavaScript in web browsers – for example, Babel’s REPL.

-

There are also native apps and IDE plugins for running JavaScript.

Consoles often run in non-strict mode

In modern JavaScript, most code (e.g., modules) is executed in strict mode. However, consoles often run in non-strict mode. Therefore, you may occasionally get slightly different results when using a console to execute code from this book.

10.2 The console.* API: printing data and more

In browsers, the console is something you can bring up that is normally hidden. For Node.js, the console is the terminal that Node.js is currently running in.

The full console.* API is documented on MDN web docs and on the Node.js website. It is not part of the JavaScript language standard, but much functionality is supported by both browsers and Node.js.

In this chapter, we only look at the following two methods for printing data (“printing” means displaying in the console):

-

console.log() -

console.error()

10.2.1 Printing values: console.log() (stdout)

There are two variants of this operation:

console.log(...values: Array<any>): void

console.log(pattern: string, ...values: Array<any>): void

10.2.1.1 Printing multiple values

The first variant prints (text representations of) values on the console:

console.log('abc', 123, true);

Output:

abc 123 true

At the end, console.log() always prints a newline. Therefore, if you call it with zero arguments, it just prints a newline.

10.2.1.2 Printing a string with substitutions

The second variant performs string substitution:

console.log('Test: %s %j', 123, 'abc');

Output:

Test: 123 "abc"

These are some of the directives you can use for substitutions:

-

%sconverts the corresponding value to a string and inserts it.console.log('%s %s', 'abc', 123);Output:

abc 123 -

%oinserts a string representation of an object.console.log('%o', {foo: 123, bar: 'abc'});Output:

{ foo: 123, bar: 'abc' } -

%jconverts a value to a JSON string and inserts it.console.log('%j', {foo: 123, bar: 'abc'});Output:

{"foo":123,"bar":"abc"} -

%%inserts a single%.console.log('%s%%', 99);Output:

99%

10.2.2 Printing error information: console.error() (stderr)

console.error() works the same as console.log(), but what it logs is considered error information. For Node.js, that means that the output goes to stderr instead of stdout on Unix.

10.2.3 Printing nested objects via JSON.stringify()

JSON.stringify() is occasionally useful for printing nested objects:

console.log(JSON.stringify({first: 'Jane', last: 'Doe'}, null, 2));

Output:

{"first": "Jane","last": "Doe"}