22. Generators

- 22.1. Overview

- 22.1.1. What are generators?

- 22.1.2. Kinds of generators

- 22.1.3. Use case: implementing iterables

- 22.1.4. Use case: simpler asynchronous code

- 22.1.5. Use case: receiving asynchronous data

- 22.2. What are generators?

- 22.2.1. Roles played by generators

- 22.3. Generators as iterators (data production)

- 22.3.1. Ways of iterating over a generator

- 22.3.2. Returning from a generator

- 22.3.3. Throwing an exception from a generator

- 22.3.4. Example: iterating over properties

- 22.3.5. You can only

yieldin generators - 22.3.6. Recursion via

yield*

- 22.4. Generators as observers (data consumption)

- 22.4.1. Sending values via

next() - 22.4.2.

yieldbinds loosely - 22.4.3.

return()andthrow() - 22.4.4.

return()terminates the generator - 22.4.5.

throw()signals an error - 22.4.6. Example: processing asynchronously pushed data

- 22.4.7.

yield*: the full story

- 22.4.1. Sending values via

- 22.5. Generators as coroutines (cooperative multitasking)

- 22.5.1. The full generator interface

- 22.5.2. Cooperative multitasking

- 22.5.3. The limitations of cooperative multitasking via generators

- 22.6. Examples of generators

- 22.6.1. Implementing iterables via generators

- 22.6.2. Generators for lazy evaluation

- 22.6.3. Cooperative multi-tasking via generators

- 22.7. Inheritance within the iteration API (including generators)

- 22.7.1.

IteratorPrototype - 22.7.2. The value of

thisin generators

- 22.7.1.

- 22.8. Style consideration: whitespace before and after the asterisk

- 22.8.1. Generator function declarations and expressions

- 22.8.2. Generator method definitions

- 22.8.3. Formatting recursive

yield - 22.8.4. Documenting generator functions and methods

- 22.9. FAQ: generators

- 22.9.1. Why use the keyword

function*for generators and notgenerator? - 22.9.2. Is

yielda keyword?

- 22.9.1. Why use the keyword

- 22.10. Conclusion

- 22.11. Further reading

22.1 Overview

22.1.1 What are generators?

You can think of generators as processes (pieces of code) that you can pause and resume:

function* genFunc() {

// (A)

console.log('First');

yield;

console.log('Second');

}

Note the new syntax: function* is a new “keyword” for generator functions (there are also generator methods). yield is an operator with which a generator can pause itself. Additionally, generators can also receive input and send output via yield.

When you call a generator function genFunc(), you get a generator object genObj that you can use to control the process:

const genObj = genFunc();

The process is initially paused in line A. genObj.next() resumes execution, a yield inside genFunc() pauses execution:

genObj.next();

// Output: First

genObj.next();

// output: Second

22.1.2 Kinds of generators

There are four kinds of generators:

- Generator function declarations:

function*genFunc(){···}constgenObj=genFunc(); - Generator function expressions:

constgenFunc=function*(){···};constgenObj=genFunc(); - Generator method definitions in object literals:

constobj={*generatorMethod(){···}};constgenObj=obj.generatorMethod(); - Generator method definitions in class definitions (class declarations or class expressions):

classMyClass{*generatorMethod(){···}}constmyInst=newMyClass();constgenObj=myInst.generatorMethod();

22.1.3 Use case: implementing iterables

The objects returned by generators are iterable; each yield contributes to the sequence of iterated values. Therefore, you can use generators to implement iterables, which can be consumed by various ES6 language mechanisms: for-of loop, spread operator (...), etc.

The following function returns an iterable over the properties of an object, one [key, value] pair per property:

function* objectEntries(obj) {

const propKeys = Reflect.ownKeys(obj);

for (const propKey of propKeys) {

// `yield` returns a value and then pauses

// the generator. Later, execution continues

// where it was previously paused.

yield [propKey, obj[propKey]];

}

}

objectEntries() is used like this:

const jane = { first: 'Jane', last: 'Doe' };

for (const [key,value] of objectEntries(jane)) {

console.log(`${key}: ${value}`);

}

// Output:

// first: Jane

// last: Doe

How exactly objectEntries() works is explained in a dedicated section. Implementing the same functionality without generators is much more work.

22.1.4 Use case: simpler asynchronous code

You can use generators to tremendously simplify working with Promises. Let’s look at a Promise-based function fetchJson() and how it can be improved via generators.

function fetchJson(url) {

return fetch(url)

.then(request => request.text())

.then(text => {

return JSON.parse(text);

})

.catch(error => {

console.log(`ERROR: ${error.stack}`);

});

}

With the library co and a generator, this asynchronous code looks synchronous:

const fetchJson = co.wrap(function* (url) {

try {

let request = yield fetch(url);

let text = yield request.text();

return JSON.parse(text);

}

catch (error) {

console.log(`ERROR: ${error.stack}`);

}

});

ECMAScript 2017 will have async functions which are internally based on generators. With them, the code looks like this:

async function fetchJson(url) {

try {

let request = await fetch(url);

let text = await request.text();

return JSON.parse(text);

}

catch (error) {

console.log(`ERROR: ${error.stack}`);

}

}

All versions can be invoked like this:

fetchJson('http://example.com/some_file.json')

.then(obj => console.log(obj));

22.1.5 Use case: receiving asynchronous data

Generators can receive input from next() via yield. That means that you can wake up a generator whenever new data arrives asynchronously and to the generator it feels like it receives the data synchronously.

22.2 What are generators?

Generators are functions that can be paused and resumed (think cooperative multitasking or coroutines), which enables a variety of applications.

As a first example, consider the following generator function whose name is genFunc:

function* genFunc() {

// (A)

console.log('First');

yield; // (B)

console.log('Second'); // (C)

}

Two things distinguish genFunc from a normal function declaration:

- It starts with the “keyword”

function*. - It can pause itself, via

yield(line B).

Calling genFunc does not execute its body. Instead, you get a so-called generator object, with which you can control the execution of the body:

genFunc() is initially suspended before the body (line A). The method call genObj.next() continues execution until the next yield:

As you can see in the last line, genObj.next() also returns an object. Let’s ignore that for now. It will matter later.

genFunc is now paused in line B. If we call next() again, execution resumes and line C is executed:

Afterwards, the function is finished, execution has left the body and further calls of genObj.next() have no effect.

22.2.1 Roles played by generators

Generators can play three roles:

- Iterators (data producers): Each

yieldcan return a value vianext(), which means that generators can produce sequences of values via loops and recursion. Due to generator objects implementing the interfaceIterable(which is explained in the chapter on iteration), these sequences can be processed by any ECMAScript 6 construct that supports iterables. Two examples are:for-ofloops and the spread operator (...). - Observers (data consumers):

yieldcan also receive a value fromnext()(via a parameter). That means that generators become data consumers that pause until a new value is pushed into them vianext(). - Coroutines (data producers and consumers): Given that generators are pausable and can be both data producers and data consumers, not much work is needed to turn them into coroutines (cooperatively multitasked tasks).

The next sections provide deeper explanations of these roles.

22.3 Generators as iterators (data production)

As explained before, generator objects can be data producers, data consumers or both. This section looks at them as data producers, where they implement both the interfaces Iterable and Iterator (shown below). That means that the result of a generator function is both an iterable and an iterator. The full interface of generator objects will be shown later.

interface Iterable {

[Symbol.iterator]() : Iterator;

}

interface Iterator {

next() : IteratorResult;

}

interface IteratorResult {

value : any;

done : boolean;

}

I have omitted method return() of interface Iterable, because it is not relevant in this section.

A generator function produces a sequence of values via yield, a data consumer consumes thoses values via the iterator method next(). For example, the following generator function produces the values 'a' and 'b':

function* genFunc() {

yield 'a';

yield 'b';

}

This interaction shows how to retrieve the yielded values via the generator object genObj:

22.3.1 Ways of iterating over a generator

As generator objects are iterable, ES6 language constructs that support iterables can be applied to them. The following three ones are especially important.

First, the for-of loop:

for (const x of genFunc()) {

console.log(x);

}

// Output:

// a

// b

Second, the spread operator (...), which turns iterated sequences into elements of an array (consult the chapter on parameter handling for more information on this operator):

const arr = [...genFunc()]; // ['a', 'b']

Third, destructuring:

22.3.2 Returning from a generator

The previous generator function did not contain an explicit return. An implicit return is equivalent to returning undefined. Let’s examine a generator with an explicit return:

function* genFuncWithReturn() {

yield 'a';

yield 'b';

return 'result';

}

The returned value shows up in the last object returned by next(), whose property done is true:

However, most constructs that work with iterables ignore the value inside the done object:

for (const x of genFuncWithReturn()) {

console.log(x);

}

// Output:

// a

// b

const arr = [...genFuncWithReturn()]; // ['a', 'b']

yield*, an operator for making recursive generator calls, does consider values inside done objects. It is explained later.

22.3.3 Throwing an exception from a generator

If an exception leaves the body of a generator then next() throws it:

function* genFunc() {

throw new Error('Problem!');

}

const genObj = genFunc();

genObj.next(); // Error: Problem!

That means that next() can produce three different “results”:

- For an item

xin an iteration sequence, it returns{ value: x, done: false } - For the end of an iteration sequence with a return value

z, it returns{ value: z, done: true } - For an exception that leaves the generator body, it throws that exception.

22.3.4 Example: iterating over properties

Let’s look at an example that demonstrates how convenient generators are for implementing iterables. The following function, objectEntries(), returns an iterable over the properties of an object:

function* objectEntries(obj) {

// In ES6, you can use strings or symbols as property keys,

// Reflect.ownKeys() retrieves both

const propKeys = Reflect.ownKeys(obj);

for (const propKey of propKeys) {

yield [propKey, obj[propKey]];

}

}

This function enables you to iterate over the properties of an object jane via the for-of loop:

const jane = { first: 'Jane', last: 'Doe' };

for (const [key,value] of objectEntries(jane)) {

console.log(`${key}: ${value}`);

}

// Output:

// first: Jane

// last: Doe

For comparison – an implementation of objectEntries() that doesn’t use generators is much more complicated:

function objectEntries(obj) {

let index = 0;

let propKeys = Reflect.ownKeys(obj);

return {

[Symbol.iterator]() {

return this;

},

next() {

if (index < propKeys.length) {

let key = propKeys[index];

index++;

return { value: [key, obj[key]] };

} else {

return { done: true };

}

}

};

}

22.3.5 You can only yield in generators

A significant limitation of generators is that you can only yield while you are (statically) inside a generator function. That is, yielding in callbacks doesn’t work:

function* genFunc() {

['a', 'b'].forEach(x => yield x); // SyntaxError

}

yield is not allowed inside non-generator functions, which is why the previous code causes a syntax error. In this case, it is easy to rewrite the code so that it doesn’t use callbacks (as shown below). But unfortunately that isn’t always possible.

function* genFunc() {

for (const x of ['a', 'b']) {

yield x; // OK

}

}

The upside of this limitation is explained later: it makes generators easier to implement and compatible with event loops.

22.3.6 Recursion via yield*

You can only use yield within a generator function. Therefore, if you want to implement a recursive algorithm with generator, you need a way to call one generator from another one. This section shows that that is more complicated than it sounds, which is why ES6 has a special operator, yield*, for this. For now, I only explain how yield* works if both generators produce output, I’ll later explain how things work if input is involved.

How can one generator recursively call another generator? Let’s assume you have written a generator function foo:

function* foo() {

yield 'a';

yield 'b';

}

How would you call foo from another generator function bar? The following approach does not work!

function* bar() {

yield 'x';

foo(); // does nothing!

yield 'y';

}

Calling foo() returns an object, but does not actually execute foo(). That’s why ECMAScript 6 has the operator yield* for making recursive generator calls:

function* bar() {

yield 'x';

yield* foo();

yield 'y';

}

// Collect all values yielded by bar() in an array

const arr = [...bar()];

// ['x', 'a', 'b', 'y']

Internally, yield* works roughly as follows:

function* bar() {

yield 'x';

for (const value of foo()) {

yield value;

}

yield 'y';

}

The operand of yield* does not have to be a generator object, it can be any iterable:

function* bla() {

yield 'sequence';

yield* ['of', 'yielded'];

yield 'values';

}

const arr = [...bla()];

// ['sequence', 'of', 'yielded', 'values']

22.3.6.1 yield* considers end-of-iteration values

Most constructs that support iterables ignore the value included in the end-of-iteration object (whose property done is true). Generators provide that value via return. The result of yield* is the end-of-iteration value:

function* genFuncWithReturn() {

yield 'a';

yield 'b';

return 'The result';

}

function* logReturned(genObj) {

const result = yield* genObj;

console.log(result); // (A)

}

If we want to get to line A, we first must iterate over all values yielded by logReturned():

22.3.6.2 Iterating over trees

Iterating over a tree with recursion is simple, writing an iterator for a tree with traditional means is complicated. That’s why generators shine here: they let you implement an iterator via recursion. As an example, consider the following data structure for binary trees. It is iterable, because it has a method whose key is Symbol.iterator. That method is a generator method and returns an iterator when called.

class BinaryTree {

constructor(value, left=null, right=null) {

this.value = value;

this.left = left;

this.right = right;

}

/** Prefix iteration */

* [Symbol.iterator]() {

yield this.value;

if (this.left) {

yield* this.left;

// Short for: yield* this.left[Symbol.iterator]()

}

if (this.right) {

yield* this.right;

}

}

}

The following code creates a binary tree and iterates over it via for-of:

const tree = new BinaryTree('a',

new BinaryTree('b',

new BinaryTree('c'),

new BinaryTree('d')),

new BinaryTree('e'));

for (const x of tree) {

console.log(x);

}

// Output:

// a

// b

// c

// d

// e

22.4 Generators as observers (data consumption)

As consumers of data, generator objects conform to the second half of the generator interface, Observer:

interface Observer {

next(value? : any) : void;

return(value? : any) : void;

throw(error) : void;

}

As an observer, a generator pauses until it receives input. There are three kinds of input, transmitted via the methods specified by the interface:

-

next()sends normal input. -

return()terminates the generator. -

throw()signals an error.

22.4.1 Sending values via next()

If you use a generator as an observer, you send values to it via next() and it receives those values via yield:

function* dataConsumer() {

console.log('Started');

console.log(`1. ${yield}`); // (A)

console.log(`2. ${yield}`);

return 'result';

}

Let’s use this generator interactively. First, we create a generator object:

We now call genObj.next(), which starts the generator. Execution continues until the first yield, which is where the generator pauses. The result of next() is the value yielded in line A (undefined, because yield doesn’t have an operand). In this section, we are not interested in what next() returns, because we only use it to send values, not to retrieve values.

> genObj.next()

Started

{ value: undefined, done: false }

We call next() two more times, in order to send the value 'a' to the first yield and the value 'b' to the second yield:

> genObj.next('a')

1. a

{ value: undefined, done: false }

> genObj.next('b')

2. b

{ value: 'result', done: true }

The result of the last next() is the value returned from dataConsumer(). done being true indicates that the generator is finished.

Unfortunately, next() is asymmetric, but that can’t be helped: It always sends a value to the currently suspended yield, but returns the operand of the following yield.

22.4.1.1 The first next()

When using a generator as an observer, it is important to note that the only purpose of the first invocation of next() is to start the observer. It is only ready for input afterwards, because this first invocation advances execution to the first yield. Therefore, any input you send via the first next() is ignored:

function* gen() {

// (A)

while (true) {

const input = yield; // (B)

console.log(input);

}

}

const obj = gen();

obj.next('a');

obj.next('b');

// Output:

// b

Initially, execution is paused in line A. The first invocation of next():

- Feeds the argument

'a'ofnext()to the generator, which has no way to receive it (as there is noyield). That’s why it is ignored. - Advances to the

yieldin line B and pauses execution. - Returns

yield’s operand (undefined, because it doesn’t have an operand).

The second invocation of next():

- Feeds the argument

'b'ofnext()to the generator, which receives it via theyieldin line B and assigns it to the variableinput. - Then execution continues until the next loop iteration, where it is paused again, in line B.

- Then

next()returns with thatyield’s operand (undefined).

The following utility function fixes this issue:

/**

* Returns a function that, when called,

* returns a generator object that is immediately

* ready for input via `next()`

*/

function coroutine(generatorFunction) {

return function (...args) {

const generatorObject = generatorFunction(...args);

generatorObject.next();

return generatorObject;

};

}

To see how coroutine() works, let’s compare a wrapped generator with a normal one:

const wrapped = coroutine(function* () {

console.log(`First input: ${yield}`);

return 'DONE';

});

const normal = function* () {

console.log(`First input: ${yield}`);

return 'DONE';

};

The wrapped generator is immediately ready for input:

The normal generator needs an extra next() until it is ready for input:

22.4.2 yield binds loosely

yield binds very loosely, so that we don’t have to put its operand in parentheses:

yield a + b + c;

This is treated as:

yield (a + b + c);

Not as:

(yield a) + b + c;

As a consequence, many operators bind more tightly than yield and you have to put yield in parentheses if you want to use it as an operand. For example, you get a SyntaxError if you make an unparenthesized yield an operand of plus:

console.log('Hello' + yield); // SyntaxError

console.log('Hello' + yield 123); // SyntaxError

console.log('Hello' + (yield)); // OK

console.log('Hello' + (yield 123)); // OK

You do not need parens if yield is a direct argument in a function or method call:

foo(yield 'a', yield 'b');

You also don’t need parens if you use yield on the right-hand side of an assignment:

const input = yield;

22.4.2.1 yield in the ES6 grammar

The need for parens around yield can be seen in the following grammar rules in the ECMAScript 6 specification. These rules describe how expressions are parsed. I list them here from general (loose binding, lower precedence) to specific (tight binding, higher precedence). Wherever a certain kind of expression is demanded, you can also use more specific ones. The opposite is not true. The hierarchy ends with ParenthesizedExpression, which means that you can mention any expression anywhere, if you put it in parentheses.

The operands of an AdditiveExpression are an AdditiveExpression and a MultiplicativeExpression. Therefore, using a (more specific) ParenthesizedExpression as an operand is OK, but using a (more general) YieldExpression isn’t.

22.4.3 return() and throw()

Generator objects have two additional methods, return() and throw(), that are similar to next().

Let’s recap how next(x) works (after the first invocation):

- The generator is currently suspended at a

yieldoperator. - Send the value

xto thatyield, which means that it evaluates tox. - Proceed to the next

yield,returnorthrow:-

yield xleads tonext()returning with{ value: x, done: false } -

return xleads tonext()returning with{ value: x, done: true } -

throw err(not caught inside the generator) leads tonext()throwingerr.

-

return() and throw() work similarly to next(), but they do something different in step 2:

-

return(x)executesreturn xat the location ofyield. -

throw(x)executesthrow xat the location ofyield.

22.4.4 return() terminates the generator

return() performs a return at the location of the yield that led to the last suspension of the generator. Let’s use the following generator function to see how that works.

function* genFunc1() {

try {

console.log('Started');

yield; // (A)

} finally {

console.log('Exiting');

}

}

In the following interaction, we first use next() to start the generator and to proceed until the yield in line A. Then we return from that location via return().

22.4.4.1 Preventing termination

You can prevent return() from terminating the generator if you yield inside the finally clause (using a return statement in that clause is also possible):

function* genFunc2() {

try {

console.log('Started');

yield;

} finally {

yield 'Not done, yet!';

}

}

This time, return() does not exit the generator function. Accordingly, the property done of the object it returns is false.

You can invoke next() one more time. Similarly to non-generator functions, the return value of the generator function is the value that was queued prior to entering the finally clause.

22.4.4.2 Returning from a newborn generator

Returning a value from a newborn generator (that hasn’t started yet) is allowed:

22.4.5 throw() signals an error

throw() throws an exception at the location of the yield that led to the last suspension of the generator. Let’s examine how that works via the following generator function.

function* genFunc1() {

try {

console.log('Started');

yield; // (A)

} catch (error) {

console.log('Caught: ' + error);

}

}

In the following interaction, we first use next() to start the generator and proceed until the yield in line A. Then we throw an exception from that location.

> const genObj1 = genFunc1();

> genObj1.next()

Started

{ value: undefined, done: false }

> genObj1.throw(new Error('Problem!'))

Caught: Error: Problem!

{ value: undefined, done: true }

The result of throw() (shown in the last line) stems from us leaving the function with an implicit return.

22.4.5.1 Throwing from a newborn generator

Throwing an exception in a newborn generator (that hasn’t started yet) is allowed:

22.4.6 Example: processing asynchronously pushed data

The fact that generators-as-observers pause while they wait for input makes them perfect for on-demand processing of data that is received asynchronously. The pattern for setting up a chain of generators for processing is as follows:

- Each member of the chain of generators (except the last one) has a parameter

target. It receives data viayieldand sends data viatarget.next(). - The last member of the chain of generators has no parameter

targetand only receives data.

The whole chain is prefixed by a non-generator function that makes an asynchronous request and pushes the results into the chain of generators via next().

As an example, let’s chain generators to process a file that is read asynchronously.

The following code sets up the chain: it contains the generators splitLines, numberLines and printLines. Data is pushed into the chain via the non-generator function readFile.

readFile(fileName, splitLines(numberLines(printLines())));

I’ll explain what these functions do when I show their code.

As previously explained, if generators receive input via yield, the first invocation of next() on the generator object doesn’t do anything. That’s why I use the previously shown helper function coroutine() to create coroutines here. It executes the first next() for us.

readFile() is the non-generator function that starts everything:

import {createReadStream} from 'fs';

/**

* Creates an asynchronous ReadStream for the file whose name

* is `fileName` and feeds it to the generator object `target`.

*

* @see ReadStream https://nodejs.org/api/fs.html#fs_class_fs_readstream

*/

function readFile(fileName, target) {

const readStream = createReadStream(fileName,

{ encoding: 'utf8', bufferSize: 1024 });

readStream.on('data', buffer => {

const str = buffer.toString('utf8');

target.next(str);

});

readStream.on('end', () => {

// Signal end of output sequence

target.return();

});

}

The chain of generators starts with splitLines:

/**

* Turns a sequence of text chunks into a sequence of lines

* (where lines are separated by newlines)

*/

const splitLines = coroutine(function* (target) {

let previous = '';

try {

while (true) {

previous += yield;

let eolIndex;

while ((eolIndex = previous.indexOf('\n')) >= 0) {

const line = previous.slice(0, eolIndex);

target.next(line);

previous = previous.slice(eolIndex+1);

}

}

} finally {

// Handle the end of the input sequence

// (signaled via `return()`)

if (previous.length > 0) {

target.next(previous);

}

// Signal end of output sequence

target.return();

}

});

Note an important pattern:

-

readFileuses the generator object methodreturn()to signal the end of the sequence of chunks that it sends. -

readFilesends that signal whilesplitLinesis waiting for input viayield, inside an infinite loop.return()breaks from that loop. -

splitLinesuses afinallyclause to handle the end-of-sequence.

The next generator is numberLines:

//**

* Prefixes numbers to a sequence of lines

*/

const numberLines = coroutine(function* (target) {

try {

for (const lineNo = 0; ; lineNo++) {

const line = yield;

target.next(`${lineNo}: ${line}`);

}

} finally {

// Signal end of output sequence

target.return();

}

});

The last generator is printLines:

/**

* Receives a sequence of lines (without newlines)

* and logs them (adding newlines).

*/

const printLines = coroutine(function* () {

while (true) {

const line = yield;

console.log(line);

}

});

The neat thing about this code is that everything happens lazily (on demand): lines are split, numbered and printed as they arrive; we don’t have to wait for all of the text before we can start printing.

22.4.7 yield*: the full story

As a rough rule of thumb, yield* performs (the equivalent of) a function call from one generator (the caller) to another generator (the callee).

So far, we have only seen one aspect of yield: it propagates yielded values from the callee to the caller. Now that we are interested in generators receiving input, another aspect becomes relevant: yield* also forwards input received by the caller to the callee. In a way, the callee becomes the active generator and can be controlled via the caller’s generator object.

22.4.7.1 Example: yield* forwards next()

The following generator function caller() invokes the generator function callee() via yield*.

function* callee() {

console.log('callee: ' + (yield));

}

function* caller() {

while (true) {

yield* callee();

}

}

callee logs values received via next(), which allows us to check whether it receives the value 'a' and 'b' that we send to caller.

throw() and return() are forwarded in a similar manner.

22.4.7.2 The semantics of yield* expressed in JavaScript

I’ll explain the complete semantics of yield* by showing how you’d implemented it in JavaScript.

The following statement:

let yieldStarResult = yield* calleeFunc();

is roughly equivalent to:

let yieldStarResult;

const calleeObj = calleeFunc();

let prevReceived = undefined;

while (true) {

try {

// Forward input previously received

const {value,done} = calleeObj.next(prevReceived);

if (done) {

yieldStarResult = value;

break;

}

prevReceived = yield value;

} catch (e) {

// Pretend `return` can be caught like an exception

if (e instanceof Return) {

// Forward input received via return()

calleeObj.return(e.returnedValue);

return e.returnedValue; // “re-throw”

} else {

// Forward input received via throw()

calleeObj.throw(e); // may throw

}

}

}

To keep things simple, several things are missing in this code:

- The operand of

yield*can be any iterable value. -

return()andthrow()are optional iterator methods. We should only call them if they exist. - If an exception is received and

throw()does not exist, butreturn()does thenreturn()is called (before throwing an exception) to givecalleeObjectthe opportunity to clean up. -

calleeObjcan refuse to close, by returning an object whose propertydoneisfalse. Then the caller also has to refuse to close andyield*must continue to iterate.

22.5 Generators as coroutines (cooperative multitasking)

We have seen generators being used as either sources or sinks of data. For many applications, it’s good practice to strictly separate these two roles, because it keeps things simpler. This section describes the full generator interface (which combines both roles) and one use case where both roles are needed: cooperative multitasking, where tasks must be able to both send and receive information.

22.5.1 The full generator interface

The full interface of generator objects, Generator, handles both output and input:

interface Generator {

next(value? : any) : IteratorResult;

throw(value? : any) : IteratorResult;

return(value? : any) : IteratorResult;

}

interface IteratorResult {

value : any;

done : boolean;

}

The interface Generator combines two interfaces that we have seen previously: Iterator for output and Observer for input.

interface Iterator { // data producer

next() : IteratorResult;

return?(value? : any) : IteratorResult;

}

interface Observer { // data consumer

next(value? : any) : void;

return(value? : any) : void;

throw(error) : void;

}

22.5.2 Cooperative multitasking

Cooperative multitasking is an application of generators where we need them to handle both output and input. Before we get into how that works, let’s first review the current state of parallelism in JavaScript.

JavaScript runs in a single process. There are two ways in which this limitation is being abolished:

- Multiprocessing: Web Workers let you run JavaScript in multiple processes. Shared access to data is one of the biggest pitfalls of multiprocessing. Web Workers avoid it by not sharing any data. That is, if you want a Web Worker to have a piece of data, you must send it a copy or transfer your data to it (after which you can’t access it anymore).

- Cooperative multitasking: There are various patterns and libraries that experiment with cooperative multitasking. Multiple tasks are run, but only one at a time. Each task must explicitly suspend itself, giving it full control over when a task switch happens. In these experiments, data is often shared between tasks. But due to explicit suspension, there are few risks.

Two use cases benefit from cooperative multitasking, because they involve control flows that are mostly sequential, anyway, with occasional pauses:

-

Streams: A task sequentially processes a stream of data and pauses if there is no data available.

- For binary streams, WHATWG is currently working on a standard proposal that is based on callbacks and Promises.

- For streams of data, Communicating Sequential Processes (CSP) are an interesting solution. A generator-based CSP library is covered later in this chapter.

-

Asynchronous computations: A task blocks (pauses) until it receives the result of a long- running computation.

- In JavaScript, Promises have become a popular way of handling asynchronous computations. Support for them is included in ES6. The next section explains how generators can make using Promises simpler.

22.5.2.1 Simplifying asynchronous computations via generators

Several Promise-based libraries simplify asynchronous code via generators. Generators are ideal as clients of Promises, because they can be suspended until a result arrives.

The following example demonstrates what that looks like if one uses the library co by T.J. Holowaychuk. We need two libraries (if we run Node.js code via babel-node):

import fetch from 'isomorphic-fetch';

const co = require('co');

co is the actual library for cooperative multitasking, isomorphic-fetch is a polyfill for the new Promise-based fetch API (a replacement of XMLHttpRequest; read “That’s so fetch!” by Jake Archibald for more information). fetch makes it easy to write a function getFile that returns the text of a file at a url via a Promise:

function getFile(url) {

return fetch(url)

.then(request => request.text());

}

We now have all the ingredients to use co. The following task reads the texts of two files, parses the JSON inside them and logs the result.

co(function* () {

try {

const [croftStr, bondStr] = yield Promise.all([ // (A)

getFile('http://localhost:8000/croft.json'),

getFile('http://localhost:8000/bond.json'),

]);

const croftJson = JSON.parse(croftStr);

const bondJson = JSON.parse(bondStr);

console.log(croftJson);

console.log(bondJson);

} catch (e) {

console.log('Failure to read: ' + e);

}

});

Note how nicely synchronous this code looks, even though it makes an asynchronous call in line A. A generator-as-task makes an async call by yielding a Promise to the scheduler function co. The yielding pauses the generator. Once the Promise returns a result, the scheduler resumes the generator by passing it the result via next(). A simple version of co looks as follows.

function co(genFunc) {

const genObj = genFunc();

step(genObj.next());

function step({value,done}) {

if (!done) {

// A Promise was yielded

value

.then(result => {

step(genObj.next(result)); // (A)

})

.catch(error => {

step(genObj.throw(error)); // (B)

});

}

}

}

I have ignored that next() (line A) and throw() (line B) may throw exceptions (whenever an exception escapes the body of the generator function).

22.5.3 The limitations of cooperative multitasking via generators

Coroutines are cooperatively multitasked tasks that have no limitations: Inside a coroutine, any function can suspend the whole coroutine (the function activation itself, the activation of the function’s caller, the caller’s caller, etc.).

In contrast, you can only suspend a generator from directly within a generator and only the current function activation is suspended. Due to these limitations, generators are occasionally called shallow coroutines [3].

22.5.3.1 The benefits of the limitations of generators

The limitations of generators have two main benefits:

- Generators are compatible with event loops, which provide simple cooperative multitasking in browsers. I’ll explain the details momentarily.

- Generators are relatively easy to implement, because only a single function activation needs to be suspended and because browsers can continue to use event loops.

JavaScript already has a very simple style of cooperative multitasking: the event loop, which schedules the execution of tasks in a queue. Each task is started by calling a function and finished once that function is finished. Events, setTimeout() and other mechanisms add tasks to the queue.

This style of multitasking makes one important guarantee: run to completion; every function can rely on not being interrupted by another task until it is finished. Functions become transactions and can perform complete algorithms without anyone seeing the data they operate on in an intermediate state. Concurrent access to shared data makes multitasking complicated and is not allowed by JavaScript’s concurrency model. That’s why run to completion is a good thing.

Alas, coroutines prevent run to completion, because any function could suspend its caller. For example, the following algorithm consists of multiple steps:

If step2 was to suspend the algorithm, other tasks could run before the last step of the algorithm is performed. Those tasks could contain other parts of the application which would see sharedData in an unfinished state. Generators preserve run to completion, they only suspend themselves and return to their caller.

co and similar libraries give you most of the power of coroutines, without their disadvantages:

- They provide schedulers for tasks defined via generators.

- Tasks “are” generators and can thus be fully suspended.

- A recursive (generator) function call is only suspendable if it is done via

yield*. That gives callers control over suspension.

22.6 Examples of generators

This section gives several examples of what generators can be used for.

22.6.1 Implementing iterables via generators

In the chapter on iteration, I implemented several iterables “by hand”. In this section, I use generators, instead.

22.6.1.1 The iterable combinator take()

take() converts a (potentially infinite) sequence of iterated values into a sequence of length n:

function* take(n, iterable) {

for (const x of iterable) {

if (n <= 0) return;

n--;

yield x;

}

}

The following is an example of using it:

const arr = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'];

for (const x of take(2, arr)) {

console.log(x);

}

// Output:

// a

// b

An implementation of take() without generators is more complicated:

function take(n, iterable) {

const iter = iterable[Symbol.iterator]();

return {

[Symbol.iterator]() {

return this;

},

next() {

if (n > 0) {

n--;

return iter.next();

} else {

maybeCloseIterator(iter);

return { done: true };

}

},

return() {

n = 0;

maybeCloseIterator(iter);

}

};

}

function maybeCloseIterator(iterator) {

if (typeof iterator.return === 'function') {

iterator.return();

}

}

Note that the iterable combinator zip() does not profit much from being implemented via a generator, because multiple iterables are involved and for-of can’t be used.

22.6.1.2 Infinite iterables

naturalNumbers() returns an iterable over all natural numbers:

function* naturalNumbers() {

for (let n=0;; n++) {

yield n;

}

}

This function is often used in conjunction with a combinator:

for (const x of take(3, naturalNumbers())) {

console.log(x);

}

// Output

// 0

// 1

// 2

Here is the non-generator implementation, so you can compare:

function naturalNumbers() {

let n = 0;

return {

[Symbol.iterator]() {

return this;

},

next() {

return { value: n++ };

}

}

}

22.6.1.3 Array-inspired iterable combinators: map, filter

Arrays can be transformed via the methods map and filter. Those methods can be generalized to have iterables as input and iterables as output.

22.6.1.3.1 A generalized map()

This is the generalized version of map:

function* map(iterable, mapFunc) {

for (const x of iterable) {

yield mapFunc(x);

}

}

map() works with infinite iterables:

22.6.1.3.2 A generalized filter()

This is the generalized version of filter:

function* filter(iterable, filterFunc) {

for (const x of iterable) {

if (filterFunc(x)) {

yield x;

}

}

}

filter() works with infinite iterables:

22.6.2 Generators for lazy evaluation

The next two examples show how generators can be used to process a stream of characters.

- The input is a stream of characters.

- Step 1 – tokenizing (characters → words): The characters are grouped into words, strings that match the regular expression

/^[A-Za-z0-9]+$/. Non-word characters are ignored, but they separate words. The input of this step is a stream of characters, the output a stream of words. - Step 2 – extracting numbers (words → numbers): only keep words that match the regular expression

/^[0-9]+$/and convert them to numbers. - Step 3 – adding numbers (numbers → numbers): for every number received, return the total received so far.

The neat thing is that everything is computed lazily (incrementally and on demand): computation starts as soon as the first character arrives. For example, we don’t have to wait until we have all characters to get the first word.

22.6.2.1 Lazy pull (generators as iterators)

Lazy pull with generators works as follows. The three generators implementing steps 1–3 are chained as follows:

addNumbers(extractNumbers(tokenize(CHARS)))

Each of the chain members pulls data from a source and yields a sequence of items. Processing starts with tokenize whose source is the string CHARS.

22.6.2.1.1 Step 1 – tokenizing

The following trick makes the code a bit simpler: the end-of-sequence iterator result (whose property done is false) is converted into the sentinel value END_OF_SEQUENCE.

/**

* Returns an iterable that transforms the input sequence

* of characters into an output sequence of words.

*/

function* tokenize(chars) {

const iterator = chars[Symbol.iterator]();

let ch;

do {

ch = getNextItem(iterator); // (A)

if (isWordChar(ch)) {

let word = '';

do {

word += ch;

ch = getNextItem(iterator); // (B)

} while (isWordChar(ch));

yield word; // (C)

}

// Ignore all other characters

} while (ch !== END_OF_SEQUENCE);

}

const END_OF_SEQUENCE = Symbol();

function getNextItem(iterator) {

const {value,done} = iterator.next();

return done ? END_OF_SEQUENCE : value;

}

function isWordChar(ch) {

return typeof ch === 'string' && /^[A-Za-z0-9]$/.test(ch);

}

How is this generator lazy? When you ask it for a token via next(), it pulls its iterator (lines A and B) as often as needed to produce as token and then yields that token (line C). Then it pauses until it is again asked for a token. That means that tokenization starts as soon as the first characters are available, which is convenient for streams.

Let’s try out tokenization. Note that the spaces and the dot are non-words. They are ignored, but they separate words. We use the fact that strings are iterables over characters (Unicode code points). The result of tokenize() is an iterable over words, which we turn into an array via the spread operator (...).

22.6.2.1.2 Step 2 – extracting numbers

This step is relatively simple, we only yield words that contain nothing but digits, after converting them to numbers via Number().

/**

* Returns an iterable that filters the input sequence

* of words and only yields those that are numbers.

*/

function* extractNumbers(words) {

for (const word of words) {

if (/^[0-9]+$/.test(word)) {

yield Number(word);

}

}

}

You can again see the laziness: If you ask for a number via next(), you get one (via yield) as soon as one is encountered in words.

Let’s extract the numbers from an Array of words:

Note that strings are converted to numbers.

22.6.2.1.3 Step 3 – adding numbers

/**

* Returns an iterable that contains, for each number in

* `numbers`, the total sum of numbers encountered so far.

* For example: 7, 4, -1 --> 7, 11, 10

*/

function* addNumbers(numbers) {

let result = 0;

for (const n of numbers) {

result += n;

yield result;

}

}

Let’s try a simple example:

> [...addNumbers([5, -2, 12])]

[ 5, 3, 15 ]

22.6.2.1.4 Pulling the output

On its own, the chain of generator doesn’t produce output. We need to actively pull the output via the spread operator:

const CHARS = '2 apples and 5 oranges.';

const CHAIN = addNumbers(extractNumbers(tokenize(CHARS)));

console.log([...CHAIN]);

// [ 2, 7 ]

The helper function logAndYield allows us to examine whether things are indeed computed lazily:

function* logAndYield(iterable, prefix='') {

for (const item of iterable) {

console.log(prefix + item);

yield item;

}

}

const CHAIN2 = logAndYield(addNumbers(extractNumbers(tokenize(logAndYield(CHA\

RS)))), '-> ');

[...CHAIN2];

// Output:

// 2

//

// -> 2

// a

// p

// p

// l

// e

// s

//

// a

// n

// d

//

// 5

//

// -> 7

// o

// r

// a

// n

// g

// e

// s

// .

The output shows that addNumbers produces a result as soon as the characters '2' and ' ' are received.

22.6.2.2 Lazy push (generators as observables)

Not much work is needed to convert the previous pull-based algorithm into a push-based one. The steps are the same. But instead of finishing via pulling, we start via pushing.

As previously explained, if generators receive input via yield, the first invocation of next() on the generator object doesn’t do anything. That’s why I use the previously shown helper function coroutine() to create coroutines here. It executes the first next() for us.

The following function send() does the pushing.

/**

* Pushes the items of `iterable` into `sink`, a generator.

* It uses the generator method `next()` to do so.

*/

function send(iterable, sink) {

for (const x of iterable) {

sink.next(x);

}

sink.return(); // signal end of stream

}

When a generator processes a stream, it needs to be aware of the end of the stream, so that it can clean up properly. For pull, we did this via a special end-of-stream sentinel. For push, the end-of-stream is signaled via return().

Let’s test send() via a generator that simply outputs everything it receives:

/**

* This generator logs everything that it receives via `next()`.

*/

const logItems = coroutine(function* () {

try {

while (true) {

const item = yield; // receive item via `next()`

console.log(item);

}

} finally {

console.log('DONE');

}

});

Let’s send logItems() three characters via a string (which is an iterable over Unicode code points).

22.6.2.2.1 Step 1 – tokenize

Note how this generator reacts to the end of the stream (as signaled via return()) in two finally clauses. We depend on return() being sent to either one of the two yields. Otherwise, the generator would never terminate, because the infinite loop starting in line A would never terminate.

/**

* Receives a sequence of characters (via the generator object

* method `next()`), groups them into words and pushes them

* into the generator `sink`.

*/

const tokenize = coroutine(function* (sink) {

try {

while (true) { // (A)

let ch = yield; // (B)

if (isWordChar(ch)) {

// A word has started

let word = '';

try {

do {

word += ch;

ch = yield; // (C)

} while (isWordChar(ch));

} finally {

// The word is finished.

// We get here if

// - the loop terminates normally

// - the loop is terminated via `return()` in line C

sink.next(word); // (D)

}

}

// Ignore all other characters

}

} finally {

// We only get here if the infinite loop is terminated

// via `return()` (in line B or C).

// Forward `return()` to `sink` so that it is also

// aware of the end of stream.

sink.return();

}

});

function isWordChar(ch) {

return /^[A-Za-z0-9]$/.test(ch);

}

This time, the laziness is driven by push: as soon as the generator has received enough characters for a word (in line C), it pushes the word into sink (line D). That is, the generator does not wait until it has received all characters.

tokenize() demonstrates that generators work well as implementations of linear state machines. In this case, the machine has two states: “inside a word” and “not inside a word”.

Let’s tokenize a string:

22.6.2.2.2 Step 2 – extract numbers

This step is straightforward.

/**

* Receives a sequence of strings (via the generator object

* method `next()`) and pushes only those strings to the generator

* `sink` that are “numbers” (consist only of decimal digits).

*/

const extractNumbers = coroutine(function* (sink) {

try {

while (true) {

const word = yield;

if (/^[0-9]+$/.test(word)) {

sink.next(Number(word));

}

}

} finally {

// Only reached via `return()`, forward.

sink.return();

}

});

Things are again lazy: as soon as a number is encountered, it is pushed to sink.

Let’s extract the numbers from an Array of words:

Note that the input is a sequence of strings, while the output is a sequence of numbers.

22.6.2.2.3 Step 3 – add numbers

This time, we react to the end of the stream by pushing a single value and then closing the sink.

/**

* Receives a sequence of numbers (via the generator object

* method `next()`). For each number, it pushes the total sum

* so far to the generator `sink`.

*/

const addNumbers = coroutine(function* (sink) {

let sum = 0;

try {

while (true) {

sum += yield;

sink.next(sum);

}

} finally {

// We received an end-of-stream

sink.return(); // signal end of stream

}

});

Let’s try out this generator:

22.6.2.2.4 Pushing the input

The chain of generators starts with tokenize and ends with logItems, which logs everything it receives. We push a sequence of characters into the chain via send:

const INPUT = '2 apples and 5 oranges.';

const CHAIN = tokenize(extractNumbers(addNumbers(logItems())));

send(INPUT, CHAIN);

// Output

// 2

// 7

// DONE

The following code proves that processing really happens lazily:

const CHAIN2 = tokenize(extractNumbers(addNumbers(logItems({ prefix: '-> ' })\

)));

send(INPUT, CHAIN2, { log: true });

// Output

// 2

//

// -> 2

// a

// p

// p

// l

// e

// s

//

// a

// n

// d

//

// 5

//

// -> 7

// o

// r

// a

// n

// g

// e

// s

// .

// DONE

The output shows that addNumbers produces a result as soon as the characters '2' and ' ' are pushed.

22.6.3 Cooperative multi-tasking via generators

22.6.3.1 Pausing long-running tasks

In this example, we create a counter that is displayed on a web page. We improve an initial version until we have a cooperatively multitasked version that doesn’t block the main thread and the user interface.

This is the part of the web page in which the counter should be displayed:

<body>

Counter: <span id="counter"></span>

</body>

This function displays a counter that counts up forever5:

function countUp(start = 0) {

const counterSpan = document.querySelector('#counter');

while (true) {

counterSpan.textContent = String(start);

start++;

}

}

If you ran this function, it would completely block the user interface thread in which it runs and its tab would become unresponsive.

Let’s implement the same functionality via a generator that periodically pauses via yield (a scheduling function for running this generator is shown later):

function* countUp(start = 0) {

const counterSpan = document.querySelector('#counter');

while (true) {

counterSpan.textContent = String(start);

start++;

yield; // pause

}

}

Let’s add one small improvement. We move the update of the user interface to another generator, displayCounter, which we call via yield*. As it is a generator, it can also take care of pausing.

function* countUp(start = 0) {

while (true) {

start++;

yield* displayCounter(start);

}

}

function* displayCounter(counter) {

const counterSpan = document.querySelector('#counter');

counterSpan.textContent = String(counter);

yield; // pause

}

Lastly, this is a scheduling function that we can use to run countUp(). Each execution step of the generator is handled by a separate task, which is created via setTimeout(). That means that the user interface can schedule other tasks in between and will remain responsive.

function run(generatorObject) {

if (!generatorObject.next().done) {

// Add a new task to the event queue

setTimeout(function () {

run(generatorObject);

}, 1000);

}

}

With the help of run, we get a (nearly) infinite count-up that doesn’t block the user interface:

run(countUp());

22.6.3.2 Cooperative multitasking with generators and Node.js-style callbacks

If you call a generator function (or method), it does not have access to its generator object; its this is the this it would have if it were a non-generator function. A work-around is to pass the generator object into the generator function via yield.

The following Node.js script uses this technique, but wraps the generator object in a callback (next, line A). It must be run via babel-node.

import {readFile} from 'fs';

const fileNames = process.argv.slice(2);

run(function* () {

const next = yield;

for (const f of fileNames) {

const contents = yield readFile(f, { encoding: 'utf8' }, next);

console.log('##### ' + f);

console.log(contents);

}

});

In line A, we get a callback that we can use with functions that follow Node.js callback conventions. The callback uses the generator object to wake up the generator, as you can see in the implementation of run():

function run(generatorFunction) {

const generatorObject = generatorFunction();

// Step 1: Proceed to first `yield`

generatorObject.next();

// Step 2: Pass in a function that the generator can use as a callback

function nextFunction(error, result) {

if (error) {

generatorObject.throw(error);

} else {

generatorObject.next(result);

}

}

generatorObject.next(nextFunction);

// Subsequent invocations of `next()` are triggered by `nextFunction`

}

22.6.3.3 Communicating Sequential Processes (CSP)

The library js-csp brings Communicating Sequential Processes (CSP) to JavaScript, a style of cooperative multitasking that is similar to ClojureScript’s core.async and Go’s goroutines. js-csp has two abstractions:

- Processes: are cooperatively multitasked tasks and implemented by handing a generator function to the scheduling function

go(). - Channels: are queues for communication between processes. Channels are created by calling

chan().

As an example, let’s use CSP to handle DOM events, in a manner reminiscent of Functional Reactive Programming. The following code uses the function listen() (which is shown later) to create a channel that outputs mousemove events. It then continuously retrieves the output via take, inside an infinite loop. Thanks to yield, the process blocks until the channel has output.

import csp from 'js-csp';

csp.go(function* () {

const element = document.querySelector('#uiElement1');

const channel = listen(element, 'mousemove');

while (true) {

const event = yield csp.take(channel);

const x = event.layerX || event.clientX;

const y = event.layerY || event.clientY;

element.textContent = `${x}, ${y}`;

}

});

listen() is implemented as follows.

function listen(element, type) {

const channel = csp.chan();

element.addEventListener(type,

event => {

csp.putAsync(channel, event);

});

return channel;

}

22.7 Inheritance within the iteration API (including generators)

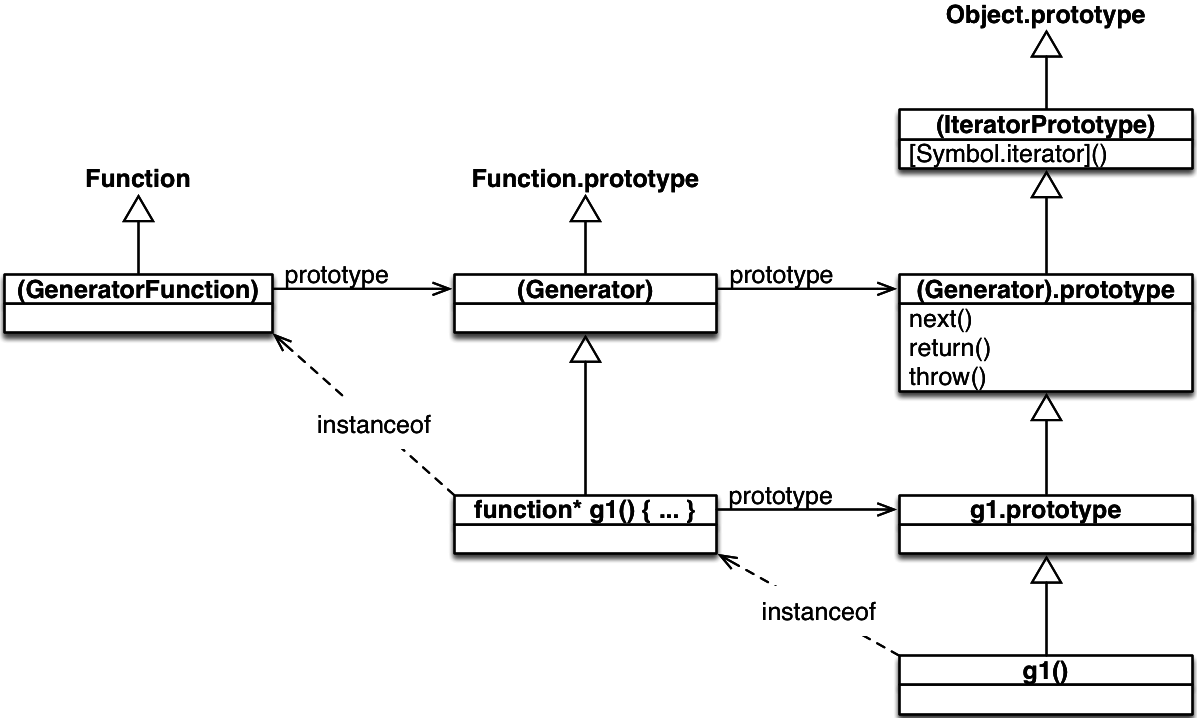

This is a diagram of how various objects are connected in ECMAScript 6 (it is based on Allen Wirf-Brock’s diagram in the ECMAScript specification):

Legend:

- The white (hollow) arrows express the has-prototype relationship (inheritance) between objects. In other words: a white arrow from

xtoymeans thatObject.getPrototypeOf(x) === y. - Parentheses indicate that an object exists, but is not accessible via a global variable.

- An

instanceofarrow fromxtoymeans thatx instanceof y.- Remember that

o instanceof Cis equivalent toC.prototype.isPrototypeOf(o).

- Remember that

- A

prototypearrow fromxtoymeans thatx.prototype === y. - The right column shows an instance with its prototypes, the middle column shows a function and its prototypes, the left column shows classes for functions (metafunctions, if you will), connected via a subclass-of relationship.

The diagram reveals two interesting facts:

First, a generator function g works very much like a constructor (however, you can’t invoke it via new; that causes a TypeError): The generator objects it creates are instances of it, methods added to g.prototype become prototype methods, etc.:

> function* g() {}

> g.prototype.hello = function () { return 'hi!'};

> const obj = g();

> obj instanceof g

true

> obj.hello()

'hi!'

Second, if you want to make methods available for all generator objects, it’s best to add them to (Generator).prototype. One way of accessing that object is as follows:

const Generator = Object.getPrototypeOf(function* () {});

Generator.prototype.hello = function () { return 'hi!'};

const generatorObject = (function* () {})();

generatorObject.hello(); // 'hi!'

22.7.1 IteratorPrototype

There is no (Iterator) in the diagram, because no such object exists. But, given how instanceof works and because (IteratorPrototype) is a prototype of g1(), you could still say that g1() is an instance of Iterator.

All iterators in ES6 have (IteratorPrototype) in their prototype chain. That object is iterable, because it has the following method. Therefore, all ES6 iterators are iterable (as a consequence, you can apply for-of etc. to them).

[Symbol.iterator]() {

return this;

}

The specification recommends to use the following code to access (IteratorPrototype):

const proto = Object.getPrototypeOf.bind(Object);

const IteratorPrototype = proto(proto([][Symbol.iterator]()));

You could also use:

const IteratorPrototype = proto(proto(function* () {}.prototype));

Quoting the ECMAScript 6 specification:

ECMAScript code may also define objects that inherit from

IteratorPrototype. TheIteratorPrototypeobject provides a place where additional methods that are applicable to all iterator objects may be added.

IteratorPrototype will probably become directly accessible in an upcoming version of ECMAScript and contain tool methods such as map() and filter() (source).

22.7.2 The value of this in generators

A generator function combines two concerns:

- It is a function that sets up and returns a generator object.

- It contains the code that the generator object steps through.

That’s why it’s not immediately obvious what the value of this should be inside a generator.

In function calls and method calls, this is what it would be if gen() wasn’t a generator function, but a normal function:

function* gen() {

'use strict'; // just in case

yield this;

}

// Retrieve the yielded value via destructuring

const [functionThis] = gen();

console.log(functionThis); // undefined

const obj = { method: gen };

const [methodThis] = obj.method();

console.log(methodThis === obj); // true

If you access this in a generator that was invoked via new, you get a ReferenceError (source: ES6 spec):

function* gen() {

console.log(this); // ReferenceError

}

new gen();

A work-around is to wrap the generator in a normal function that hands the generator its generator object via next(). That means that the generator must use its first yield to retrieve its generator object:

const generatorObject = yield;

22.8 Style consideration: whitespace before and after the asterisk

Reasonable – and legal – variations of formatting the asterisk are:

- A space before and after it:

function * foo(x, y) { ··· } - A space before it:

function *foo(x, y) { ··· } - A space after it:

function* foo(x, y) { ··· } - No whitespace before and after it:

function*foo(x, y) { ··· }

Let’s figure out which of these variations make sense for which constructs and why.

22.8.1 Generator function declarations and expressions

Here, the star is only used because generator (or something similar) isn’t available as a keyword. If it were, then a generator function declaration would look like this:

generator foo(x, y) {

···

}

Instead of generator, ECMAScript 6 marks the function keyword with an asterisk. Thus, function* can be seen as a synonym for generator, which suggests writing generator function declarations as follows.

function* foo(x, y) {

···

}

Anonymous generator function expressions would be formatted like this:

const foo = function* (x, y) {

···

}

22.8.2 Generator method definitions

When writing generator method definitions, I recommend to format the asterisk as follows.

const obj = {

* generatorMethod(x, y) {

···

}

};

There are three arguments in favor of writing a space after the asterisk.

First, the asterisk shouldn’t be part of the method name. On one hand, it isn’t part of the name of a generator function. On the other hand, the asterisk is only mentioned when defining a generator, not when using it.

Second, a generator method definition is an abbreviation for the following syntax. (To make my point, I’m redundantly giving the function expression a name, too.)

const obj = {

generatorMethod: function* generatorMethod(x, y) {

···

}

};

If method definitions are about omitting the function keyword then the asterisk should be followed by a space.

Third, generator method definitions are syntactically similar to getters and setters (which are already available in ECMAScript 5):

const obj = {

get foo() {

···

}

set foo(value) {

···

}

};

The keywords get and set can be seen as modifiers of a normal method definition. Arguably, an asterisk is also such a modifier.

22.8.3 Formatting recursive yield

The following is an example of a generator function yielding its own yielded values recursively:

function* foo(x) {

···

yield* foo(x - 1);

···

}

The asterisk marks a different kind of yield operator, which is why the above way of writing it makes sense.

22.8.4 Documenting generator functions and methods

Kyle Simpson (@getify) proposed something interesting: Given that we often append parentheses when we write about functions and methods such as Math.max(), wouldn’t it make sense to prepend an asterisk when writing about generator functions and methods? For example: should we write *foo() to refer to the generator function in the previous subsection? Let me argue against that.

When it comes to writing a function that returns an iterable, a generator is only one of the several options. I think it is better to not give away this implementation detail via marked function names.

Furthermore, you don’t use the asterisk when calling a generator function, but you do use parentheses.

Lastly, the asterisk doesn’t provide useful information – yield* can also be used with functions that return an iterable. But it may make sense to mark the names of functions and methods (including generators) that return iterables. For example, via the suffix Iter.

22.9 FAQ: generators

22.9.1 Why use the keyword function* for generators and not generator?

Due to backward compatibility, using the keyword generator wasn’t an option. For example, the following code (a hypothetical ES6 anonymous generator expression) could be an ES5 function call followed by a code block.

generator (a, b, c) {

···

}

I find that the asterisk naming scheme extends nicely to yield*.

22.9.2 Is yield a keyword?

yield is only a reserved word in strict mode. A trick is used to bring it to ES6 sloppy mode: it becomes a contextual keyword, one that is only available inside generators.

22.10 Conclusion

I hope that this chapter convinced you that generators are a useful and versatile tool.

I like that generators let you implement cooperatively multitasked tasks that block while making asynchronous function calls. In my opinion that’s the right mental model for async calls. Hopefully, JavaScript goes further in this direction in the future.

22.11 Further reading

Sources of this chapter:

[1] “Async Generator Proposal” by Jafar Husain

[2] “A Curious Course on Coroutines and Concurrency” by David Beazley

[3] “Why coroutines won’t work on the web” by David Herman